“Marcy Breaks Up With Herself”

Posted by admin on

There’s this one show I’m obsessed with right now called 20 Below. The hosts are a Canadian couple, Anette and Steve, who go to people’s houses and the wife Anette throws out most of their stuff and the husband Steve talks to them about how it’s okay to love themselves and hate their fathers. The stuff that gets thrown out goes to Goodwill or the dump, you don’t see that part, and you don’t see the fathers either, but the mothers are usually there, often crying, saying how grateful they are. By the end of the episode, the person has only twenty “nonessential” items (20 Below referring to this ideal number and to how cold it gets, I guess, in northern Canada) and they are so happy. I feel like a new person, they say. And I think, I would be amazing as a new person. I ask my boyfriend, Josh, to nominate me, but he won’t. He says I already spend too much time at home watching television.

“Exactly,” I say. “If I was on the show, I wouldn’t do that anymore.”

Josh pauses like he wants to say something he’s probably said before, about how I need to be more proactive, how I am too preoccupied with the little things, how it’s creepy that when I have a bruise I poke it because it feels good, or whatever you call good when it’s painful.

“I’m not letting the Canadians throw away our television,” he says finally, and takes his dish to the sink and scrapes spaghetti into the disposal. Even though I’m full—especially because I’m full—I think about the bag of chips in the pantry and I want to eat them all in one sitting but I tell myself no, I tell myself, I know! I’ll write a letter to the network and I’ll get Janice to sign it, since Janice is up for just about anything. Marcy has enormous potential, I imagine writing. With a little help, Marcy could be a different person. Marcy would be better as a different person. Marcy is incapable without your help of becoming a different person. Would it be worth it to make Marcy a different person? I decide maybe I won’t write that letter after all.

I get up and wash my dish and shout at Josh, who is in the other room, that I took the garbage out while he was at work, and I’m glad that he’s put his earbuds in, glad that he can’t hear about what passes for an accomplishment some days.

*

When Josh moves out a week later, he takes the TV, the gaming console, his clothes, most of the towels, and the scented oil diffuser that I’d gotten him as a gift and only I ever used. I call my friend Janice and tell h r that the oil diffuser is gone and now the apartment smells like it used to, like there’s a damp spot moldering somewhere. “I can’t find it,” I say as I get to my knees and stretch my hand out, patting under the couch, finding only dry carpet, crumbs, a crochet hook.

“I can come over, babe,” she says. “If you’re upset.”

I sit back on my heels, feel that stretch in my arches, another good kind of pain. “Maybe I’m looking at this all wrong,” I say.

“I can com over when I get off tonight,” she says. Janice and I are cocktail waitresses at Pan’s Palace, a fancy name for a place where we wear high-waisted short shorts and tight tops. I worked last night, serving drinks, followed by having drinks at the kind of shit bar that exists for servers to blow off steam. I passed out on the couch; it wasn’t until I woke up that I saw the TV was gone.

“Maybe this is a sign,” I say, looking at the dust-free circle left by the diffuser. “One less nonessential thing.”

Janice isn’t much for signs. “You call me if you need me,” she says, and hangs up.

I take the note Josh left, some bullshit about wanting to avoid a scene but he’ll call me later, soon, he promises, and I put it in the garbage disposal, grinding it to pulp, pouring the gallon of skim milk in after it, the kind of milk he likes, horrible, thin, tinted blue like the skin over a vein.

*

The one-bedroom apartment feels empty without Josh but also lighter, room in the closet where the towels were, room on the coffee table where the television was, room in my chest now that the bad thing I knew would happen has happened. I make a piece of cinnamon sugar toast and microwave some old coffee. Without the non-essential TV, I start an episode of 20 Below on my laptop. This episode, a woman who owns a two-bedroom house in Quebec has been nominated by her sister. Even though this woman is a successful veterinarian, her home is a “filthy mess,” “dark pit,” and “constant source of despair for the rest of the family” (so says the judgmental sister). Anette and Steve are on the job.

There are two parts of the show that I love best. One is when they first get to the house or apartment and the person who lives there has to show them each room.

This is when you find out how ready the subject is to go through this process, how eager they are for help, how bad they’ve let things get. The veterinarian is embarrassed as she shows Anette the bedroom, but she tries to play it off with humor. The closet is empty, hangers clacking, because clothes are piled on two chairs: the dirty chair and the clean chair. “At least there’s a system,” the woman says with a strained laugh and Anette smiles, tight-lipped.

“These are kitchen chairs,” Anette says. Anette has very dark hair that frames her pale face with very straight bangs. She always carries a clipboard. In the veterinarian’s living room, a small saucepan is being used as a candle holder. Wax fills the pot halfway. I love it. Anette does not. Anette gives the veterinarian her version of a compliment: “You are disorganized and chaotic. But you are not dirty.” I crunch through my cinnamon toast. I shake my head gently. They have a lot of work ahead of them to get down to twenty items.

“I don’t think I can do it,” the veterinarian says. “I don’t think it’s reasonable.”

“Imagine,” Anette says, “that you are a hunter-gatherer and you can only keep what you can carry your back.”

The veterinarian nods but, though I love the show, I find this particular argument unconvincing. I am not a hunter-gatherer. I would die as a hunter-gatherer.

Yes, Anette says, you would. But at least you’d lose some of that weight first.

*

Steve is talking to the veterinarian about her relationship with her sister when my mother calls to see how I’m doing.

“How are you doing?” she says.

“I’m fine,” I say. “I’m thinking of getting rid of a bunch of my shit.”

“I saw a documentary about how Goodwill throws out ninety percent of donations.”

“I don’t think that’s true,” I say. It might be true. But I’m not trying to pick a fight. “If you could only keep like twenty things, what do you think you would keep?”

“My passport,” she says.

“But like, nonessential things.”

“Your father.”

My mother thinks she’s very funny so, as a punishment for her and a treat to myself, I don’t tell her that Josh has left me.

When I hang up, with the show still paused, the apartment is very quiet. The damp spot is starting to itch me from the inside. I can smell it. I check the corners of the room and under the couch again. Fine fine fine, I hum to myself. Everything is fine fine fine. The chips are in the pantry but I won’t eat them. The damp spot is all in my head.

(I know that smell is coming from somewhere. I just have to find it.)

*

I put on an apron and a pink bandana and get a box of trash bags, the thick black ones strong enough to hide liquor bottles and bodies. I start in the kitchen because that is where Anette and Steve always start. Not many sentimental items in the kitchen. Besides, Anette isn’t a monster. A lot in a kitchen is essential. A small frying pan, a large frying pan, and a large pot: essential. Six plates, bowls, spoons, forks, knives: essential. The juicer: nonessential. I put it in a cardboard box on which I’ve written SHIT WEIGHING YOU DOWN!!!! in Sharpie, which everyone knows is the pen you use when you mean business. The juicer is technically Josh’s, so that one feels good. Two nonessential pans follow. My mother got me an Instapot for Christmas because she said I should learn to cook, except Instapots aren’t about learning to cook. They are about learning how to take shortcuts to avoid learning how to cook, which is why I am the perfect person to own an Instapot. Steve is not a fan of shortcuts. I put it in the box.

By the time I’m done in the kitchen, there is only one nonessential thing I’ve kept. It’s a mug, white with a blue drawing of a duck. The duck has completely round eyes, like it’s terrified or high, and on the side of the mug it says Le Canard, which I have always assumed but never confirmed is French for duck. I found it in a thrift store while I was in college and I remember realizing that I could simply buy it, that I didn’t need to drink out of mugs I’d stolen from the dining hall. I’d taken it home and set it lovingly on the shelf over my desk, twisting it so that the duck had its round eyes on me. I take the mug now into the living room and put it on the empty shelf I’ve designated for my twenty items.

“One,” I say.

In the kitchen, I pick up the box and the bottom of it splits because really, what was I thinking putting that much in the box w en I have these trash bags? A wine-glass shatters on the kitchen tile and I stand still for a moment, an island surrounded by an ocean of glass, sure I’ll cut myself, wishing there was someone to hear me call for help.

*

how u doin babe still okay?

Janice is a very good friend.

soooo good! I reply. cleaned out kitchen going to tackle bedroom. stopped looking for damp spot!!

That last one is a bit of a lie. Janice texts me back a face with its brain exploding out the top. Janice knows when I’m full of shit. Then she says, c u at work tmr and I push that right out of my mind, it’s an eternity before I have to go to work, and besides, by then I’ll probably be someone who enjoys her job.

No, actually, I’ll never enjoy working at Pan’s Palace.

*

I admit, I lose a bit of steam in the bedroom. Bedrooms are harder. I know what Anette would say. She’d tell me that pushing through this feeling shows I’m serious about the process. Steve would say that I deserve to be loved despite my imperfections, which isn’t as helpful, but I’ll take it. I imperfectly stuff a bunch of clothes into a trash bag. A little black dress that hasn’t fit in a few years. A T-shirt that rides up too high, exposing the tops of my hips. A jaunty cap that has never looked good on me, not even in the store, but I bought it anyway and I didn’t know why I was doing it even then. A gray turtleneck that makes my tits look enormous, but at least it hides your stomach. That is exactly the kind of shit I need to get rid of. I pull the ties on the trash bag so hard that one tears off.

Anette looks at me with disapproval. This is a meditative process, she says. Stop being such a fucking spaz.

I look into my closet for more to get rid of. Anette says that essential clothing has to be defined by the individual. A businesswoman will need different shoes than a nurse. My waitressing shoes are black sneakers with thick tread and thick soles and still my feet always ache at the end of the night. I put them in a corner with my uniform: two pairs of black shorts, two pairs of ankle-high black socks, three tight white t-shirts with the Pan’s Palace logo splashed large across the front. I always scrub baking soda into the armpits before I wash them to try to get out the stains.

The other categories of essential clothing that Anette recognizes are sleepwear, formal wear, and casual. I put a sports bra, tank top, and set of boy shorts next to my uniform for sleepwear.

I know what to do next. I’ve seen Anette do it many times. Remove each item one by one, try it on, decide if it really fits, admit if you haven’t worn it in a year. I hold up a dress I like, blue with small white flowers, a scoop neck and flouncy hem, and I decide I am not quite ready for this. I don’t want to know if it doesn’t fit, suddenly I know it won’t fit, there’s that itchy feeling back again, and I put the dress back because I’ll definitely deal with this later. And it isn’t like I should be throwing clothes away willy nilly. Unlike that veterinarian, I’m not made of money.

Even though my bedroom is by no means stripped down to essentials, I add three more items to my non-essential shelf. First, a blue vase my college boyfriend made me in a ceramics class, the glaze done to look like the vase had been broken and then glued back together. My stuffed animal Heather the narwhal, who, with Josh gone, will sleep under my arm again. A heavy iron bottle opener in the shape of a mermaid that I stole from a vintage shop downtown. Josh once asked me where I got it and I made up a lie and then hid it in my underwear drawer.

There’s a full-length mirror in the living room. It was Josh’s and I’m surprised he left it. He liked to look at himself before he went to work. Once, when we were high, he made me sit in front of it with him even though he knew I hate to look at myself in the mirror.

“Sometimes,” he said, “it’s like I am not sure I exist. It’s like I need to see myself in the mirror to be sure I’m still here.”

I turn the mirror to face the wall. When I’m a new person, looking at myself in the mirror is exactly the kind of thing I’ll like to do.

*

By midnight, I’ve filled a lot of trash bags. I’m exhausted and nowhere near having only twenty nonessential items.How does anyone do this when they have to go through a whole house? I turn on another episode of the show. Obviously, I’ve seen all of them already, but that’s not the point. Besides, I notice new things every time. I said before I love two things about 20 Below? The second is what happens at the very end of each episode, after the veterinarian—or chef or teacher or urban planner—has discovered how much happier they are to be a new person. In the final two minutes or so of the show, either Anette or Steve reveals one of their twenty below. This episode, it’s Anette’s turn.

When it comes to her twenty, Anette is pretty pragmatic. She has a whittling set (which is a bunch of small things, but in one box, so it’s okay). A pair of jade earrings that were her mom’s. A fishing pole. And my favorite thing of hers so far, a plastic Mickey Mouse that fits in the palm of her hand. Its ears have been rubbed so many times the black has worn off, revealing the flesh-colored plastic beneath. Anette is not one to make a fuss, but you can see on her face when she holds it, she loves it, and so I love it too.

Only three seasons of 20 Below have come out, six episodes each, which means they’ve shared eighteen of the forty total nonessential items. It’s very exciting. I used to talk to Josh about it, speculating about what the other twenty-two items might be and worrying that the show would be canceled before we saw them all.

“You know it’s probably bullshit, right?” Josh said. “Those people are making all this money from this show. There’s no way they actually only have like two space heaters and a cupcake tin.”

I told him he didn’t know anything at all about anything and left the room.

There are many signs that a relationship will not work out. This was one of them.

*

Though I’m planning to get up early and keep working, I sleep late and barely have time to stuff my car full of trash bags before I drive to lunch with my mother. We meet at a fish taco place and on the wall is a painting of a smiling fish nestled in a tortilla.

“Do you think that fish knows he’s about to be eaten alive?” I ask my mother.

“Do we have to talk about that every time we eat here?” she says. We each bite our tacos, cabbage and white sauce falling out the ends.

Mom has never been one to fill a silence. It’s her superpower, and so I blurt out, “Josh broke up with me,” even though I’d planned to roll it out at the very end of the meal when she’d have no time to comment. I always do this. Speak before I want to, admit what I don’t want to.

“Oh Marcy,” she says, and I hear it exactly the way she means it.

“He was beating me,” I say.

“No he wasn’t.”

“It wasn’t working. He liked cooking shows and said he didn’t understand why anyone would want to get a tattoo.”

Mom shakes her head and takes another bite of taco.

“He didn’t like that I slept in so much. But you have to when you wait tables.”

“I actually had something I wanted to discuss with you today,” she says, after dabbing the corners of her mouth with a clean napkin. My napkin is in a shredded, sticky ball. “Your father and I are selling the house.”

“The house?” I say. “My house?”

“Our house. The house you haven’t lived in in years. We put it on the market a while ago and now we have a buyer. We’re selling it and moving to Las Cruces. Your father wants to start painting.”

“You love that house,” I say.

“It’s a house.” Mom sighs. “Dear.” She takes my hand. “Your father and I are ready for a change.” I imagine Anette and Steve rubbing their hands together, the entire house disappearing until there is nothing but black garbage bags. “We knew you’d be upset,” she says.

“I’m not upset about the house. I’m upset about Josh,” I say. I tell her I can’t believe how incredibly unsupportive she’s being right now.

Mom tells me we’ll talk about this again soon because she needs me to clean my boxes out of the garage. “Maybe you and your brothers can get a storage unit together.”

“I’m decluttering my life!” I’m being too loud. The fish on the wall is meeting his death with a lot more dignity than I’m displaying. “And I’m throwing away the Instapot.”

“You should at least offer it to Josh first,” she says.

I hope she knows that sometimes she’s a bitch.

*

I’d expected to feel happy as I dropped my bags off at the Goodwill, but lunch has ruined my moment of triumph. I carry one of the bags in the front door and an elderly employee tells me no, donations go around the back, and when I take my car around I see a pile of things by a locked metal door. Most people who donate aren’t as organized as me. There’s a doll lying inside a lamp shade. An open plastic tub filled with VHS tapes.

A toaster oven still full of crumbs. I lean my bags against the wall. I’m sweating when I’m finally done unloading everything. In my purse, my phone chimes.

sorry i had to end things that way. i hope you know i care about you

I don’t text him back.

my mom is selling our house so they can move to las cruces, I text Janice.

las cruces is dope, she says.

Janice doesn’t get it. I don’t know if I get it. The house was a cramped place for three kids and it’s too big for just my parents. The upstairs hall was narrow and dark and the stairs were covered in a red-orange carpet that came off on my socks and burned my knees when I tripped. The backyard was nice but my dad was always ripping it up to try a new kind of grass, and the grass always died. In Las Cruces, they’ll have a rock garden and plant a cactus or two. When I come to visit, maybe we’ll eat dinner outside. Deserts get cold quickly when the sun sets. In fact, that’s exactly what my dad will say. “Can’t believe how quickly it gets cold when the sun’sdown!”

And we’ll nod and say, yes, how amazing.

“It’s so great when you have time to visit,” Mom will say.

And it will be great, because by then I’ll be a different person.

*

It’s 2:00 when I get home. I should be at work by 5:00. I open a beer and don’t drink it. I pour a glass of water on the carpet to make a wet spot and I rub it hard over and over with a towel until I soak up every drop, until you can barely tell it’s there. I smell it and it smells like damp carpet. Nothing sinister. Somehow, the apartment doesn’t look noticeably more empty, even after all that work. I am going to do a little more cleaning, straighten things up, and instead I lie down on the couch and open my laptop and take a sip of that beer after all. I look up 20 Below on YouTube and find a new interview, or at least one I haven’t seen before. It’s just Steve, which is unusual. Anette is the forceful personality. She’s the one who gets things done, who people make into memes. Anette holding a dustpan full of dog hair saying THIS IS YOUR LIFE. Anette opening a closet and being hit in the head with a soccer ball. Sometimes I think Steve is there because Anette doesn’t know what to do with people once she’s made them cry.

In this interview, Steve is in his blue plaid shirt and jeans. You get to know their outfits really well, because they don’t have many, and this is one of my favorites because it brings out his eyes. It’s some Canadian show and the woman interviewing him looks high school young. She asks Steve what advice he has for young people who are just starting out, who are making “home spaces” for the first time.

“That’s a great question,” Steve says. He’d say that no matter what. “As we get older, items we purchase begin to have less meaning. They’re functional rather than sentimental. I’d say, as a young person just starting out, buy only what you really, really plan to keep. Would you be willing to move with it? Because you’ll have to. Again and again. But I’ll also say, if you do own something you love, that you can tell a story about, don’t let anyone tell you to get rid of it or tell you it’s trash. Hold on to it.”

The girl nods, her face serious, and doesn’t ask the obvious follow up question. What has Anette made you give away that you regret?

*

It’s 4:30 which means I’m already late. My head feels heavy in that way I recognize. It would be so easy to lie on my bed and call in sick. Lie on the bed and not make the call at all. I would be too embarrassed to stay home if I knew Josh was getting off work in an hour. I would know that if I did crawl under the covers, Josh would come sit beside me on the bed and stroke my hair and ask if I was feeling okay.

Okay, no. No, no, no. Fucking Steve is in my head, sensitive Steve who I imagine oiling his little league glove one last time before donating it to some sick kid. Steve and the action figure he kept in its box for as long as he could stand before he got it out and played with it, before Anette made him give it to an orphan. Steve is no help. I need Anette.

You really do, she says.

My uniform is still on the floor of the bedroom and I pick it up, strip to my underwear. I always feel a twinge of anxiety before I put on the shorts and shirt. The uniform is intentionally “form fitting,” says my manager.

“Slutty,” says Janice.

You know you’re on the verge, Anette says.

I pull the shorts on and button and zip. Are they tighter than usual? They feel too tight.

You’ve probably gained weight, Anette says.

I haven’t, though. I wore these forty-eight hours ago. Nothing changes that fast.

Forty-eight hours ago you had a boyfriend and your parents still owned their house.

The button is digging into my stomach. It itches, I swear, it feels all wrong. My stomach rises a little over the waist band. Does it always? I rip them off and try on the other pair and I think it’s worse, like they both shrunk in the dryer. I don’t remember putting them in the dryer. I walk to the kitchen to get scissors, still in my underwear, the blinds open, but I don’t care, and I pick up the shorts and carve into them, cut each leg of the short from top to bottom and I do the same to the other pair. It takes force. The denim is thick and tough. Then I cut the shirts into scraps. I even cut the little ankle socks up. I almost stab the black shoes, but then I think about how they protect me, or at least they try. I put them back in the corner.

I pull armfuls of clothes from the closet. I cut the sleeves off a plain black shirt. Nothing wrong with it but nothing right either. I cut up T-shirts and running shorts and a sweatshirt that’s a little tight in the shoulders and a sweatshirt that has always fit perfectly. I cut through the closet until there is nothing left but the blue dress with the little white flowers and even though Steve would tell me not to, I cut the dress in half and one side crumples to the floor. The side still in my hand hangs limp, somehow more human now. What was I afraid of? I drop it to the floor too.

I cut off the underwear I’m in. I cut the clasp between the cups of my bra. This is good. I’m naked. I wait for the itching feeling to stop. Maybe I should burn my clothes. But burning is harder than it seems. People die in fires, cities are laid waste, and yet so little is as flammable as you hope. No way to donate them now and it’s better this way. No effort should be taken to preserve, to save them from the dump and dirt and rain and rot. It seems wrong in the middle of this mess that my skin remains unmarked. It seems wrong to leave so much of what is still wrong with me there, out in the open, when I could carve myself away, carve myself into something truly good and new.

I put the scissors on the bed and walk back to the living room. My phone is on the table. I have a text from Janice. where r u???? I turn off my phone.

You know what’s holding you back? Anette asks. I pick up the vase with the beautiful cracked glaze and drop it to the ground. I expect it to shatter, but it doesn’t. It breaks into three pieces and I pick up the smallest piece, a triangle with two sharp edges, the third edge the lip of the vase. I use it to cut open the bag of chips in the cupboard and then I bring both with me to sit in front of the full length mirror, which I turn back around.

There is something about ugliness that demands more ugliness. Why be a girl with an average face when I can be a wolfman? A creature from the black lagoon? I eat a chip. I force myself to look, to see the heavy weight of my tits, the way they don’t sag exactly, not yet, but they will. And my waist which is okay at that certain angle when I suck in a bit and arch my back and I’m doing that, arching and squirming. I let out a deep sigh, relax muscles that do not want to relax. My stomach rounds. My thighs are dimpled. I eat another chip and don’t even feel bad because I know I’m going to eat the whole bag; it was decided the moment I opened it. I look at my strange pussy with ruffled labia like a bed duster. I look at my elegant neck and strong arms and calloused feet and wide nipples. My mother’s nose and my father’s chin and my brown-green-muddled eyes that refuse to blink because if I look away for a moment I’ll look away for another month or year or lifetime. Instead I eat another chip, swipe the grease off my fingers and onto the carpet next to me. The carpet is wet next to me.

*

Is this the wet spot I made or the one I’ve been looking for?

*

I lie on the floor, the shard in my hand, looking at the shelf that now has only three nonessential items, nothing at all really. I could add some photos, I think. Or the letter my little brothers sent me when I was at camp that my mom laminated for me, so strange, so unlike her. I wonder what is in those boxes at home in the garage, if some essential part of me is buried there. Because I realize that it’s the twenty items that are essential, not the rest of it, not the pans I can replace or the oil diffuser that Josh will never use, that will force him to remember me until he finally gives it away.

*

I press the edge of the shard against my stomach and realize I have no idea how hard to press. What would be enough? What would hurt in exactly that right way, enough to distract, never enough to be seen.

Are you going to just lie there? Anette asks, and I don’t know what she’s asking. If she means get on with it. If she means get up. I can’t let her watch me doing this. She wouldn’t understand. I wish Steve were here, I think, but that’s not right either. I set the shard down. Maybe I can glue the vase back together. The best thing about it was that it already looked broken.

*

Janice arrives around midnight. She has a key and lets herself in.

“You should still be at work,” I say.

“It was slow tonight. I took first cut.”

Janice never takes first cut. She needs the money. We all do.

Janice stands still for a moment and then puts down her purse and takes the bottle of wine to the kitchen. It’s a screw top, which is good. “Where the fuck are the wineglasses?” I hear her say, and she comes back instead with two cereal bowls. She pours some wine into each bowl and sets them down next to me. Then she takes off all of her clothes. She looks right at me as she does it. Janice has dimples on her thighs too. Her waist is thin and her breasts are small and on the right one is a red-brown splash that must be a birthmark. She sits down next to me. I get up on my elbows and try to drink the wine but the angle is strange and I choke on it. Wine runs down my chin and over my breasts into my belly button and she leans over and licks a drop off my neck.

Janice grins. She takes a drink herself and doesn’t spill a drop. She takes the shard from my side and throws it across the room. She stares at me. I worry she’s in the wet spot but I don’t ask. I don’t ask if I’m fired. I don’t ask if she can see what I’ve done, what an incredible mess I’ve made. I don’t want to ever speak again. I want her to keep looking at me exactly like this: calm and wild and like she sees exactly who I am, every hidden place. I want her look at me, to be my eyes, and to never, never stop.

__________________________________

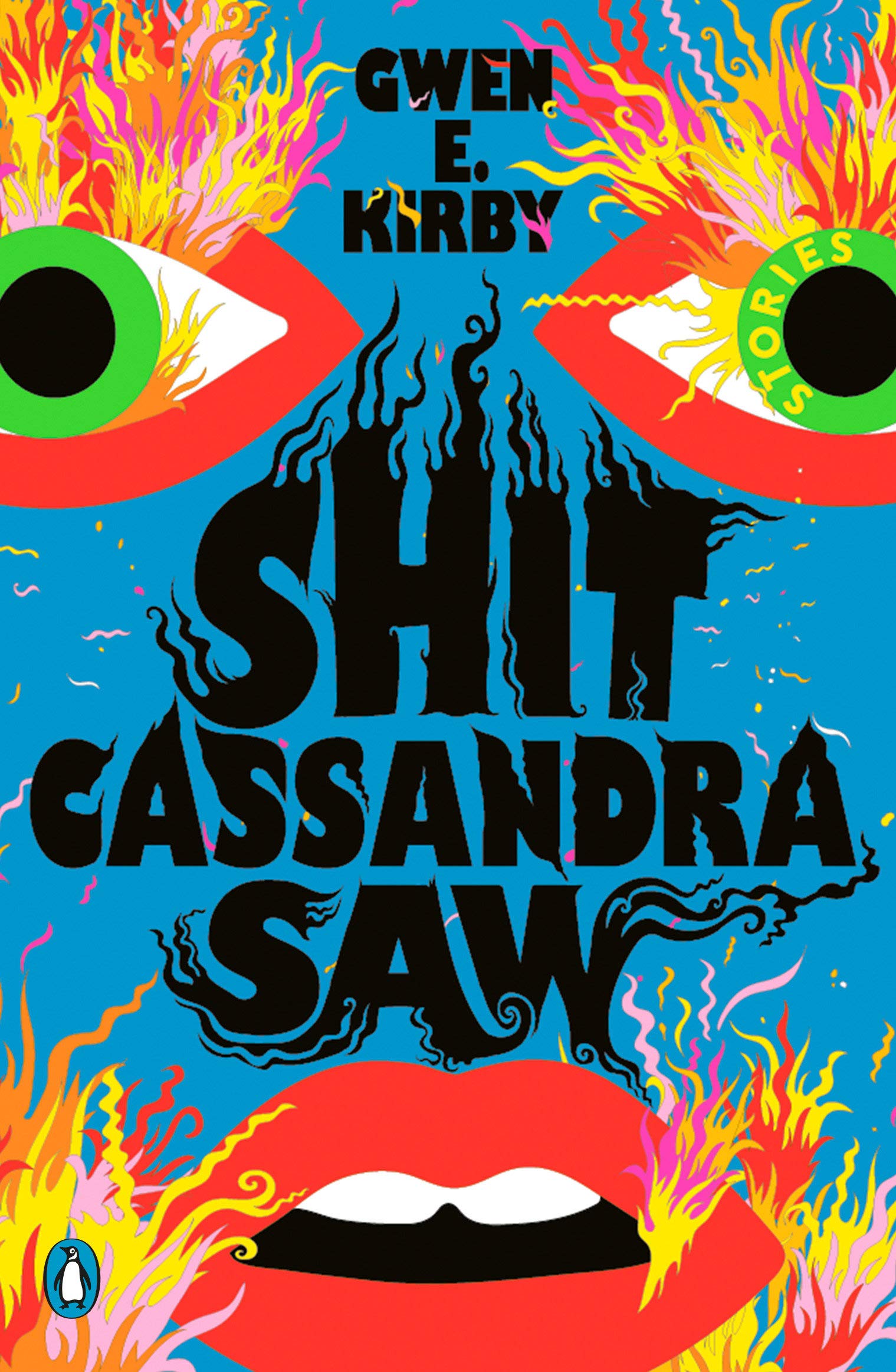

From Shit Cassandra Saw by Gwen E. Kirby, to be published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Gwen E. Kirby.